1268: Irregular Spelling: Yiddish May 31, 2018

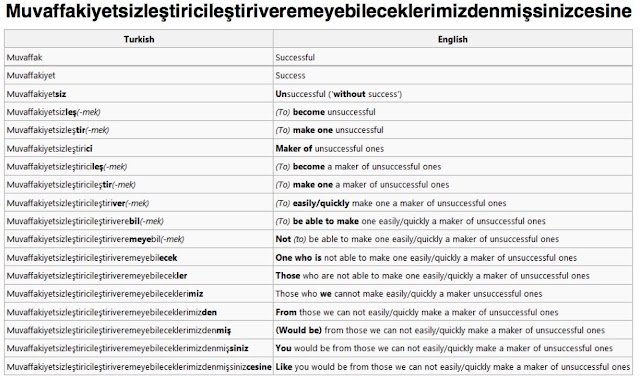

There are a lot of reasons why english spelling is so irregular, but one of them is that historically some words were adopted in (more or less) their original forms but not pronounced the same as in the native language. This happens still, especially with place-names. Nevertheless, English is by no means the only language to do so. While some languages such as Finnish borrows a lot of new words from English, the spelling always changes to fit the orthography, in other cases, such as Hebrew loan-words in Yiddish [1] they retain their original spelling. In fact, because of this, the letter ת (taw) in Hebrew is usually pronounced as [t] but in Yiddish its an [s] among other differences, such as אמת (true) pronounced 'emet' in Hebrew but 'emes' in Yiddish. This is also a problem for reading Yiddish, because while Yiddish always represents vowels, Hebrew does not often [2]. Word Facts' Podcast, only for Patreon patrons, came out today, so why not support Word Facts an