1994: Latin Sound Shifts in Modern English May 31, 2020

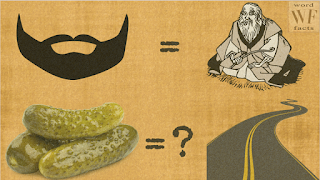

Sound shifts are not always a quick process, but looking back over time the contrasts can be quite stark. Even looking within English, the proof of Latin shifts is apparent; both the term 'corpus' and its collective plural 'corpora' are used in Modern English, and are evidence for a broader shift that happened in Latin that [s] between two vowels because a trilled [r]. Earlier, the term 'corposa' was used instead. This is not the only change that happened in Latin that carried over into English either. Support Word Facts on patreon.com/wordfacts